Advancing on MS: New drugs and hopes for a vaccine.

Advancing on MS: New drugs and hopes for a vaccine.

Philadelphia Inquirer - Philadelphia,PA,USA

Today, six drugs are approved to decrease the periodic immune attacks that underlie MS, another six are in final human testing, and dozens more are in ...

See all stories on this topic

Nutra Pharma Announces Successful Completion of 6-Month Patient ...

Business Wire (press release) - San Francisco,CA,USA

RPI-78M is ReceptoPharm's lead drug candidate for the treatment of neurological and autoimmune disorders. "This is an important milestone in our clinical ...

See all stories on this topic

Learn How To Trade Our Best Performing System – Raptor II

Trading Markets (press release) - Los Angeles,CA,USA

RPI-78M is ReceptoPharm's lead drug candidate for the treatment of neurological and autoimmune disorders. "This is an important milestone in our clinical ...

See all stories on this topic

NPHC: Completes 6-Mo. Trial Crossover for RPI-78M in ...

Trading Markets (press release) - Los Angeles,CA,USA

Nutra Pharma Corp. (NPHC) announced that its drug discovery arm, ReceptoPharm, has successfully completed its six-month patient crossover in the Phase ...

See all stories on this topic

Lilly and BioMS Medical Announce Global Licensing and Development ...

CNNMoney.com - USA

... trial in relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS). Under the terms of the agreement, Lilly and BioMS Medical will collaborate on the development of MBP8298 and ...

See all stories on this topic

Mylan And Forest Labs' Receive Final US FDA Approval For Its High ...

RTT News - Williamsville,NY,USA

... clinical trial in relapsing-remitting MS or RRMS. As per the terms of the agreement, Lilly and BioMS Medical will team up on the development of MBP8298 ...

See all stories on this topic

Market Report -- In Play (LLY)

MSN Money - USA

... progressive MS (SPMS) and one phase II clinical trial in relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS). BioMS Medical will receive an upfront payment of $87 mln, ...

See all stories on this topic

Top 7 BioPharma & Pharma Innovations of 2007

Seeking Alpha - New York,NY,USA

A metabolic parent of Wyeth's immunosuppresant sirolimus (Rapamune), Temsirolimus is an mTOR inhibitor that arrests the cell cycle at G1 in kindey tumor ...

See all stories on this topic

Genmab Announces Details Of Planned Ofatumumab Phase II Study In ...

Medical News Today (press release) - UK

Genmab A/S (OMX: GEN) announced details of a planned Phase II study of ofatumumab (HuMax-CD20(R)) for the treatment of relapsing remitting multiple ...

See all stories on this topic

Genmab Initiates Ofatumumab Study In Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

eMaxHealth.com - Hickory,NC,USA

Genmab's study centers have been initiated and are ready to enroll patients in a Phase II study of ofatumumab (HuMax-CD20) to evaluate treatment of relapsed ...

See all stories on this topic

Advancing on MS: New drugs and hopes for a vaccine.

By Marie McCullough

Inquirer Staff Writer

Barely 15 years ago, doctors could do nothing to change the course of multiple sclerosis, the disabling neurological disease that strikes in the prime of adulthood.

Today, six drugs are approved to decrease the periodic immune attacks that underlie MS, another six are in final human testing, and dozens more are in development. Researchers have zeroed in on genetic and environmental risk factors; a common virus may play a role in activating the disease. And the ultimate goal - regrowing damaged nerves - is no longer a pipe dream.

"I think a regeneration process may be available in the next five to 10 years," said Abdolmohamad Rostami, chair of neurology at Thomas Jefferson University, where researchers have partially reversed nerve damage in mice. "I'm very optimistic."

Rostami joined other MS researchers at last month's annual conference of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society's Greater Delaware Valley Chapter. It was attended by more than 2,000 patients, health-care providers and advocates.

Without being pollyannaish about the prospects for curing MS, the experts agreed that huge strides have been made in managing and slowing the disease.

"We're treating people much earlier, so they're getting more years of exacerbation-free time, which we believe will reduce the long-term disability," said Clyde Markowitz, director of the MS Center at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania.

In MS, infection-fighting white blood cells attack the protective myelin covering that insulates nerve fibers in the brain, spinal cord and eyes. Like broken electrical cables, the inflamed myelin - and, eventually, nerves - become unable to conduct the brain's signals. This can cause impaired vision, numbness, mental problems, and paralysis.

About 10 percent of patients become steadily and progressively more disabled without clear autoimmune attacks. But most of the country's 400,000 patients - 11,000 in this region - experience relapses of varying severity and frequency, with complete or partial recovery in between.

Disability accumulates over time, but MS is maddeningly unpredictable and rarely fatal in itself.

"It's been over two years since I had a flare-up," said Carol Johnson, 58, of Philadelphia.

Although she rode around last month's conference on a scooter to conserve her energy, she can still walk, 31 years after diagnosis.

"If I'm in church, I get an escort to help me," she said. "But I can get up and go to the bathroom. I'm so thankful I can still do that."

Circumstantial evidence has long supported the idea that MS is triggered by an infectious agent, perhaps a virus or bacteria, in people with genetic susceptibility.

Now, research is bolstering suspicion that Epstein-Barr virus is the culprit.

Epstein-Barr is a ubiquitious microbe that infects about 95 percent of American adults. Often there are no symptoms, but more than a third of infected adolescents and young adults develop the fever, sore throat and fatigue of infectious mononucleosis.

A history of mono increases the small risk of MS as much as threefold. Studies suggest Epstein-Barr also plays a role in lupus, another autoimmune disease.

Last year, Harvard University scientists reported using stored blood samples to show that 42 MS patients had abnormally high levels of antibodies against Epstein-Barr. The antibodies spiked 20 years before the onset of MS symptoms, then stayed high.

Another clue was published last month: Italian researchers found remnants of Epstein-Barr infection in the autopsied brain tissue of MS patients.

While the viral link is controversial, it is raising hopes that MS could be prevented with a vaccine, just like measles or polio.

"Collectively, the results . . . provide compelling evidence," said Alberto Ascherio, senior author of the Harvard study. "I think this new data on MS will generate new interest in developing a vaccine" against Epstein-Barr, he added.

Meanwhile, scientists are learning more and more about the immune system's role in MS.

The six MS drugs approved since 1993 target various molecules that enable infection-fighting blood cells - T cells and B cells - to communicate and mobilize. The challenge has been finding a way to suppress the immune system that is powerful enough to be effective in most MS patients - yet not so powerful that it leaves them vulnerable to other diseases.

Tysabri, approved in 2004, turned out to be so good at clamping down on immune cells that a few patients developed a rare, overwhelming viral infection of the brain; the drug now carries a warning.

Fingolimod, an experimental drug now in final human testing, is also designed to rein in immune cells, but earlier in the mobilization process. It keeps them from leaving the lymph nodes where they're produced.

"We're getting close to being able to control the destructive immune process," said John Richert, vice president of research at the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. "It may come at the price of side effects that are devastating. But we hope we can find a risk-benefit balance."

Whether reducing relapses will ultimately lessen patients' cumulative disability is not yet clear. But that's the hope, especially as scientists discover new molecules to manipulate.

At Jefferson, neuro-immunologist Denise Fitzgerald has shown that interleukin 27, an immune system signaling hormone isolated five years ago, can suppress an MS-like disease in mice, apparently by turning other interleukin molecules on or off.

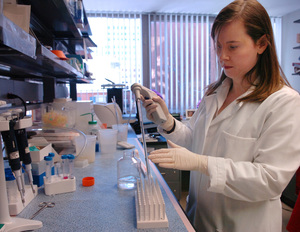

Fitzgerald, 28, has a personal reason to be passionate about her work: Seven years ago, a mysterious bout of spinal cord inflammation, perhaps triggered by an undetectable infection, turned her from an athletic doctoral student into a paraplegic - in a matter of hours.

"I was in the hospital for five weeks, on steroids. From there, I made an excellent recovery," she said. "But knowing what paralysis feels like, and how hard the recovery period is, and the exhaustion - it gives me the commitment to this research."

Commitment is crucial. Thirty years ago, a gene variant was linked to MS in about half of patients. The next major genetic advance didn't come until four months ago, when an international research team identified variants of two more genes that significantly raise the risk of MS.

"Genetic studies will eventually lead us to the cause of MS and make it easier to prevent," Richert said. "But in the short term, each of these genes offer a new therapeutic target."

Along with novel therapies, existing drugs may become part of the treatment arsenal. Among those showing promise: Daclizumab, now used to prevent kidney transplant rejection; Rituximab, approved to treat non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and the autoimmune (rheumatoid) form of arthritis; popular antidepressants known as SSRIs; and an anemia therapy called Erythropoietin.

There are clues that "natural" substances may work against MS as well. Estriol, a form of estrogen being given to women with MS in a trial led by the University of California at Los Angeles, is normally produced only during pregnancy - a time when MS often goes into remission. Vitamin D, easily derived from sun exposure, may help explain why MS is rare in equatorial countries while comparatively common in sun-deprived places such as Scandinavia.

At Jefferson, both glucosamine, the dietary supplement for joints, and a compound derived from ordinary soy have been shown to partly restore walking ability in mice with an MS-like disease.

One of the biggest obstacles to the search for new treatments has been measuring their impact in humans. That obstacle is crumbling, thanks to research led by the University of Pennsylvania and Johns Hopkins University. Scientists there have developed two simple, relatively inexpensive tests that use visual impairment as an indicator of MS nerve damage.

One test measures thinning of the eye's retinal nerve with optical coherence tomography, a machine now used for glaucoma screening. The other test evaluates eyesight using an eye chart with letters that are gray instead of the usual black. Nerve damage makes low-contrast patterns difficult for MS patients to see.

"The more brain lesions, the worse the patient's visual score," explained Penn neuro-ophthalmologist Laura J. Balcer. The new vision tests already are being used in clinical trials of new drugs.

Contact staff writer Marie McCullough at 215-854-2720 or mmccullough@phillynews.com.

SARAH J. GLOVER / Inquirer Staff Photographer

Multiple sclerosis researcher Denise Fitzgerald , working at Jefferson, has a personal reason to be passionate about the pursuit: Seven years ago, a mysterious spinal-cord inflammation temporarily left her a paraplegic.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home